Seychelles and the battle with royalty, rats, and the last truly wild places left on Earth

The Aldabra coral atoll is one of the world’s largest and reported to have been first discovered in 916AD. Image via Aldabra Islands, the company developing homes for the Qatari royal family in the Seychelles.

A Fine Line in Paradise: Bird expert Adrian Skerrett on Cautious Development in the Seychelles

An Exclusive for Green Prophet

Off the powder-soft sands and turquoise waters of the Seychelles, a quiet storm is brewing—one that involves royalty, rats, and the last truly wild places left on Earth.

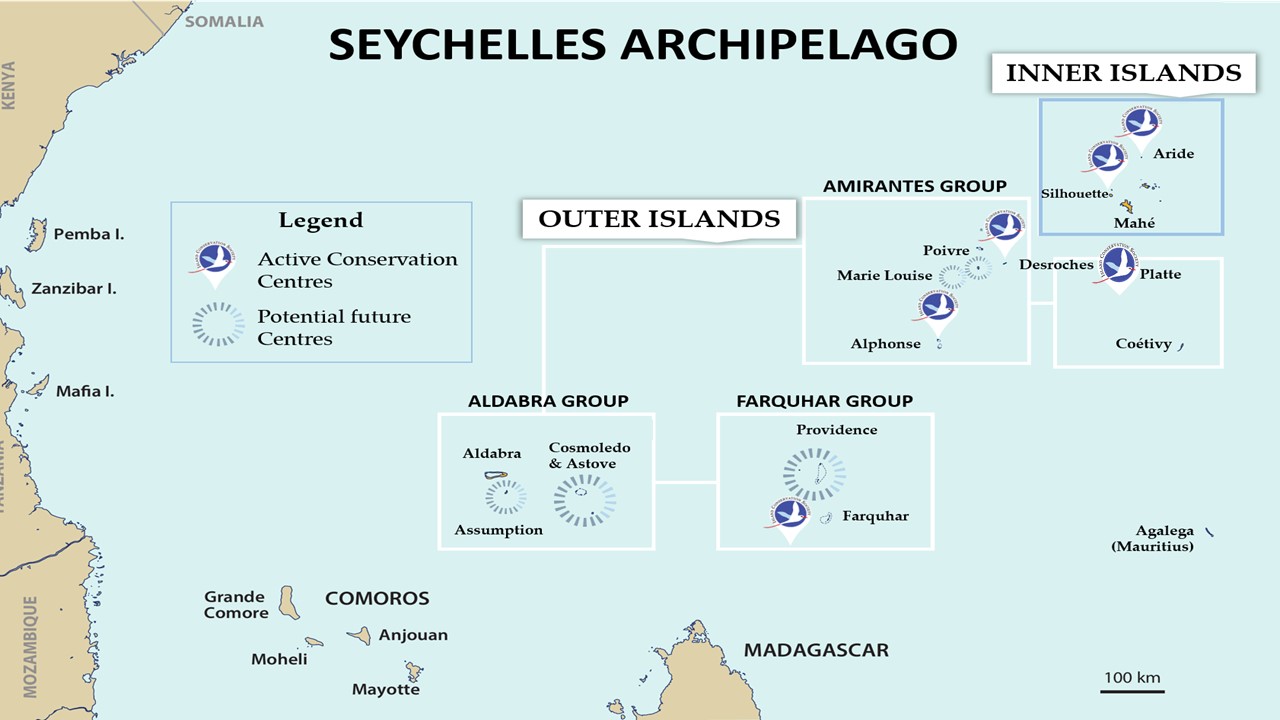

At the heart of it all is Assomption Island, a jewel of an island in the remote Aldabra Group in the Outer Seychelles islands. While its neighboring atoll, Aldabra, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site home to rare flightless birds and thousands of nesting turtles, Assomption is scarred from a history of guano mining and is now the center of a controversial luxury development funded by Qatari investors.

Adrian Skerrett, a long-time Seychelles resident on Mahé and is leading authority on its birdlife, has been watching over these islands for decades. He’s not against development but for balance. As Chairman of the Island Conservation Society and editor of a number of definitive field guides on the region’s birds, he knows the tightrope between development and destruction better than anyone.

I know that if I am going to get any reliable information from anyone, I am to speak with an animal conservationist. The best choice are birders, as they are usually elders with experience, meticulous in documentation and they have a keen sense for the beautiful and fragile balance of life on earth. As a bonus, Skerrett’

Adrian Skerret

“We’re not against development,” he tells Green Prophet. “There are positives to come out of it. Some of our most successful conservation efforts are supported by tourism—eradication of rats, monitoring of turtles, even full-time conservation staff on islands like Alphonse.”

But Assomption is differenu, he says. And its development has roused a handful of international conservation organizations who believe that the development of Assomption will lead to a catastrophic downfall of nature, a lesson like that was learned in Thailand after the movie The Beach turned Maya Beach into an over-touristed spot that devastated nature around it.

A Royal Playground Disguised as a Hotel?

Assets Group image of the ultra-wealthy development on the Seychelles Island of Assomption

The proposed resort is being developed by the Qatari Assets Development Company, part of the Assets Group, whose leadership—Moutaz and Ramez Al-Khayyat—are currently embroiled in UK lawsuits over alleged links to terrorist financing. The development, Skerrett says, is “evidently for private use, for members of the royal family.”

The concern? “There is no way on Earth this is a hotel. It makes no financial sense. The original plans were horrendous—multi-use jetties, beach vegetation cleared for views. They didn’t even know they needed planning permission.”

Despite early enthusiasm from the developers, Skerrett and his team were hired to conduct the Environmental Impact Assessment—and what they found was alarming.

“They wanted to build directly on the beach, on top of dune ecosystems. The damage had already begun before we arrived.”

Assomption once boasted one of the most significant nesting beaches for endangered hawksbill turtles. Exploitation in the 1970s saw thousands taken. Every year thousands would be culled, until they crashed and disappeared. “Turtles take 30 to 40 years to mature. It’s only now we’re starting to see the impact of what happened decades ago,” says Skerrett.

Map of the Seychelles

He recalls a previous proposal to hand Assomption over to the Indian government for use as a military base—an idea that was met with strong public and environmental resistance. “It would have been an absolute disaster,” he says. “A deep-water port, heavy infrastructure—it was horrendous.” That plan was eventually scrapped due to public outcry, but now the concern is that tourism may be used as a political mask. “There’s no way on earth this is a hotel,” Adrian says of the Qatari development. “This is clearly being built for private use. We fear it’s the lesser of two evils, but still deeply problematic.”

“This is an absolute disaster for the turtles.”

The development threatens a resurgence of turtles. Plans show construction stretching across the island’s best beaches, about a 3-mile stretch where green turtles also nest. Worse still, there’s currently no conservation presence.

“The Qataris want development along the entire stretch of beach,” says Skerret. And according to “explorer” missions by their paid Swedish photographer, they are also looking to develop projects on other tiny islands in the Seychelles.

“What we’re fighting for now is a model like Alphonse—where the investor pays a conservation levy, enabling year-round conservation presence. Without it, this becomes a private playground with no accountability.”

Conservation Requires Teeth—and Cash

Adabra Atoll and Assomption Island are about 25 miles from each other.

Skerrett and his colleagues have proposed a foundation for Assomption, merged with the existing Aldabra Foundation. This would include government representatives, NGOs, and even invite Qatari stakeholders onto the board. The goal: fund full-time staff, implement rehabilitation programs, and, critically, eradicate invasive rats.

“If you’ve ever been to a rat-free island,” he says, “you feel the difference in the whole biodiversity. Lizards, birds—rats devastate everything.”

The rats on the outer islands, he adds with a dry laugh are “Arabic rats,” while those closer to Mahé are “French.” The distinction is genetic—but poetic, given the geopolitical stakes.

Aldabra: What Could Go Wrong?

The ripple effects don’t stop at Assomption. Conservationists worry the project will increase traffic to Aldabra, potentially compromising biosecurity and fragile ecosystems.

“Jet skis are banned in the Aldabra group for a reason,” says Skerrett. “But the development plan includes a marine recreation center. We’re concerned this could bring pressure—more frequent helicopter visits, uncontrolled access, seeds on shoes, invasive species.”

The Seychelles Islands Foundation has promised oversight, but with no current supervision on Assomption and reports of construction crews already active, Skerrett is deeply uneasy.

“They initially wanted 1,500 workers. That’s insane. We said 500 max, but who knows what’s actually happening there right now.”

How You Can Help

The Island Conservation Society has established a UK-registered charity to support conservation in the Seychelles. Donations are tax-deductible, and funds go toward island-specific endowments—building a financial buffer for the future of biodiversity in the region.

For conservationists and ecotourists alike, Skerrett’s vision is clear:

“Tourism has brought us wealth, stability. You don’t see begging or homelessness here like in the West. But if we let private development run rampant, the cost will be our wildest places—and the creatures that call them home.”

As of now, Assomption Island is not permanently inhabited by a civilian population. The only people who reside on the island are a small number of personnel from the Island Development Company (IDC) who maintain the airstrip and oversee basic infrastructure.

The Islands Development Company (IDC) of Seychelles is a parastatal organization owned by the government, tasked with overseeing the sustainable development of the nation’s outer islands. The company plays a vital role in managing islands such as Alphonse, Assomption, and Farquhar, focusing on eco-tourism, conservation, and agricultural development.

The IDC is run by a board of directors, with the Chairperson, Vice-Chairperson, and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) taking on pivotal leadership roles. Cyril Bonnelame, who was appointed CEO in January 2025, leads the operational direction of the company, bringing over 25 years of experience in various sectors. The board, including directors such as Naadir Hassan (Chairperson) and Astride Tamatave (Vice-Chairperson), ensures strategic decision-making and policy implementation to align with national and environmental objectives.

There is no established community, and no public facilities like schools, hospitals, or stores. It’s a remote, environmentally sensitive island primarily used for strategic or developmental purposes—and now, under scrutiny due to proposed luxury development projects.

With limited oversight and major concerns voiced by local conservationists like Adrian Skerrett, this island could quietly become a playground for the ultra-rich without public scrutiny or ecological safeguards. The Seychelles will need collaborators with capacity in environmental journalism, field biology, drone and underwater filming, and institutional support.

In one example, the Qatar development group has hired a Swedish photographer Jesper Anhede who appears to be running around pristine islands on the Aldabra Atoll area, handling baby turtles when they are emerging from their eggs. You can see his social media posts bragging about working for wealthy Qatari developers.

It is the same pattern all over the Middle East: they bring the money and some crazy idea and a pile of European “environmentalists” quoting Attenborough and Leed-certified developers do all they can to use nature while they chase the money. We saw this in the development of Masdar in the UAU decades ago. It’s happening in Saudi Arabia with Neom, and it’s happening now with the Qatar investment in the Indian ocean.

He is working to record information for the Qataris on and around the Aldabra atoll. According to his social media profile, he is on a solo mission. We have reached out asking him about conservationists who should be working with the development crew. We have posted one video of him handling turtles.

He also writes on Instagram: “I need your help to find the best providers or builders of ultra-luxury eco-glamping camps for a small tropical island. Think of a mix of high-end safari camps worthy of receiving royalties combined with Southeast Asian islands glamping. I have some leads, but I want more options. So all contacts, referrals, or similar places for inspiration are most welcome. Thanks 🤠”

Anhede writes: Underwater photo setup and a curious male sea turtle: #assomption #aldabra #seychelles #turtle #curious

If you believe in the power of transparency and storytelling to protect fragile ecosystems, we’d love to hear from you. Let’s help the Seychelles find the right allies—journalists, scientists, conservationists, and funders—who believe that sunlight is the best disinfectant. Who’s in? [email protected]

creditSource link